Time remains in this market cycle, but expect muted returns

By this observer's reckoning, we're a little past the halfway point in the recovery from the global financial crisis (GFC).

That's not the consensus view, which instead suggests we're in the very late stages of the cycle. The economic playbook for a financial crisis recovery was articulated by Professors Reinhart and Rogoff in This Time Is Different, a stat-laden academic tome published with remarkable prescience, shortly before the GFC. The authors show that post-crisis periods are characterized by subpar growth (check), higher levels of unemployment (check), and a recovery lasting much longer than the historical norm, usually double the average-hence our assertion we're closer to the current cycle's midpoint than its end.

Traits of post-crisis market cycles include slow starts and relatively weak peak growth rates

The main culprit for the sluggish first-half growth in recoveries following extreme financial crises tends to be excessive caution and the suppression of animal spirits, as market participants place savings and balance sheet repair at the top of their list of priorities-primarily to whittle down the overabundance of debt that precipitated the crisis in the first place.

According to the professors, growth in the second half of post-crisis recoveries eventually picks up, but it peaks at disappointing levels, equal to roughly the average of prior recoveries. With that in mind, real U.S. growth might peak at 3% before the current cycle runs its course-a disappointing figure relative to history, which has frequently featured late-cycle real growth rates in the 4% to 6% range.

As a consequence of current asset valuations and this challenging outlook for economic growth, our projected five-year return forecasts for most financial markets represent roughly half their long-run averages. Broadly speaking, we expect only 4% to 6% from equities and a mere 0% to 2% from government bonds.

Stay globally diversified with an eye on relative valuations across asset classes

By historical standards, such figures seem uninspiring, but investors have virtually no control over the absolute returns a particular investment category is bound to generate. After all, any given market can go its own direction-up or down-at its own magnitude—a little or a lot—in its own time—quickly or slowly.

However, paying attention to the comparative attractiveness across asset categories offers some consolation. The art of asset allocation resides in maintaining globally diversified exposure across capital markets—finessed by favorable relative calls on the margin.

Most of the target-risk and target-date portfolios we manage maintain broad representation across asset classes over time; however, we can and do adjust portfolio composition on the periphery to reflect our comparative preferences, leaning into market segments that seem cheap and lightening up on those we deem dear.

U.S. equities no longer represent the market of choice for the marginal value buyer

In the near term, low interest rates and low inflation continue to make U.S. equities seem relatively stable; however, domestic stocks offer among the lowest expected long-run returns across the world's major equity markets. The postelection highs in U.S. equity indexes have been built on hopes of deregulation, corporate tax reform, personal tax cuts, defense spending, infrastructure initiatives, and all manner of promised policy measures, without much thought as to how or if any of these programs will materialize. At the same time, economic momentum is building outside the United States, threatening to lure the marginal investor away. Our five-year forecast for U.S. stock returns remains at roughly half the long-run average. Indeed, the U.S. equity market seems pricey relative to its international counterparts and its own history.

Developed international equities look more attractive

Relative to U.S. equities, our long-term view favors the more modest valuations residing in Europe. Although we believe growth potential in the eurozone is structurally below that of the United States, there's a strong case that European profit growth may rebound more rapidly; Europe's economic recovery is running about three years behind the United States, so in many ways it seems like getting a second chance for those who may have missed part of the U.S. equity run. In Japan, there's not much of an economic growth story to speak of, but we're optimistic about positive changes to corporate governance, particularly the prospects for rising returns on equity from globally low levels. Still, shareholders of companies in the land of the rising sun will need to plan for a long investment horizon.

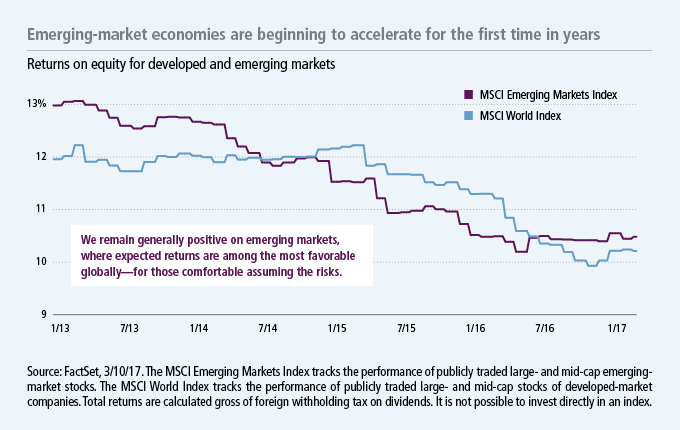

Long-run prospects for emerging-market equities outshine others—but not without risks

We remain generally positive on emerging-market equity. Our five-year expected returns for the category are among the highest globally. Valuations look more attractive than those across developed markets, especially the United States. Recent economic growth figures also reveal a burgeoning relative advantage of many emerging markets over their more mature counterparts. Caveats to our enthusiasm include the potential for renewed U.S. dollar strength, which could tighten financial conditions, and hardline U.S. protectionist trade measures, which could prompt a global growth scare. Still, it's becoming clear that the much anticipated crisis over the buildup of debt in China does not account for the offset provided by the country's sizable consumer savings. The stability of Chinese economic growth rates relative to equity valuations makes Chinese stocks attractive.

Emerging-market debt offers more promise than other fixed-income categories

Our view is that capital will flow to areas of the world that are willing to pay adequate compensation for inflation and growth risks. In that sense, our secular view of emerging-market debt is quite positive. With underlying country financials looking better than they have in decades, the asset class offers attractive coupons and remains an allocation across many of our target-date and target-risk portfolios. That said, we're mindful that a global growth scare could send investors fleeing and test the strength of many emerging economies. Still, we see real long-term value here-a relative rarity among government bond markets today. We have low but nonnegative expectations for U.S. fixed-income returns. International developed-market sovereign bond investors would do well to avoid negative yields.

Important disclosures

Important disclosures

Diversification does not guarantee a profit or eliminate the risk of a loss.

Investing involves risks, including the potential loss of principal. The stock prices of midsize and small companies can change more frequently and dramatically than those of large companies. Growth stocks may be more susceptible to earnings disappointments, and value stocks may decline in price. Large company stocks could fall out of favor, and foreign investing, especially in emerging markets, has additional risks, such as currency and market volatility and political and social instability. Fixed-income investments are subject to interest-rate and credit risk; their value will normally decline as interest rates rise or if an issuer is unable or unwilling to make principal or interest payments. Investments in higher-yielding, lower-rated securities include a higher risk of default.

MF364472